When Robert Christmas left Elizabeth, New Jersey nearly three years ago, he left behind a life of sleeping with guns by his side, dealing drugs, and couch-hopping, all his necessities for survival — but he also left behind the only life he ever knew, the only life that allowed him to “feel at home.”

Once he arrived in the Lehigh Valley, he embarked on a frightening, yet electrifying journey to change his life. After living with his girlfriend for three months, their break-up forced him to depart the blissful ignorance of the situation, realizing that he had no job, no home, and no family. His father and sister died, and his brother resided in Oregon. His life had no clear direction — his hope was slowly, yet surely diminishing, and he was couch-hopping once again, considered street-level homeless. However, he did not want to be a “burden to society,” and refused to seek help.

Christmas’ pride eventually buckled to the sheer dread of his situation. He begrudgingly admitted himself to the Rescue Mission in Allentown, a Christian-rooted organization, where he slept nightly on a cot, and received three hot meals a day.

“They’ve given me everything — shelter, food, and most definitely, brotherhood,” Christmas said. “These people have become my family here. And even though I’m Muslim, they still accepted me with open arms because we all believe in God. We all believe in hope for a greater tomorrow.”

With over a month of support from the Rescue Mission, Christmas boasts his new employment, at buffet-style restaurant Golden Corral, which he walks to, determined, almost daily. Perhaps with a few more months of support, he hopes to save enough money to rent an apartment and get ahold of his life once again.

“Pray, and be patient — just know that tomorrow is always a better day,” Christmas said.

Poverty in EHS

He would never see his dad again. When he was three years old, his father would take his final breath — a victim to liver cancer — and expel every hope for further bliss, optimism, and economic security.

Ever since that fateful day in 2006, Emmaus High School junior Robert Robinson faces the daily toll of his father’s death — both emotionally and economically. A single parent ever since, Robinson’s mom has received monthly social security checks to subsidize the loss of income for her two children, Robinson and his older sister. Although he is grateful to live in a so-called “rich” suburban neighborhood in Lower Macungie Township, he reminisces to times when his family was more economically stable.

“I think about my dad a lot, how life would be so different,” Robinson said. “We used to live in New Jersey in a huge house, much bigger than mine now. Then we moved down here because when my dad died, my mom couldn’t afford to pay for this huge house. Living in PA in the same house my whole life is so [familiar] to me, but I think about what could have been. I don’t have much of an emotional attachment to my life being so much better, but it’s on my mind a lot.”

Once Robinson celebrated his 16th birthday last June, his late father’s Social Security checks ended, snatching one of the income sources his mother relied on. After she settled for a job for the first time in 25 years, Mrs. Robinson and her family have considered alternative housing arrangements, such as renting an apartment, to make life more affordable.

Stories such as Robinson’s and Christmas’ are not uncommon among people in the Lehigh Valley, no matter the cause or severity of the circumstance. In fact, this tale of economic downturn has become much more ordinary.

The Lehigh Valley encompasses 670,000 people between Lehigh and Northampton counties, being the third most populated metropolitan area in Pennsylvania. It cultivates the nation’s 51st largest manufacturing center based on GDP, and is often flaunted as one of the top five regions in the United States in 2018, based on economic investment, job creation, and infrastructure projects, as proclaimed by Site Selection magazine’s Governor’s Cup Awards.

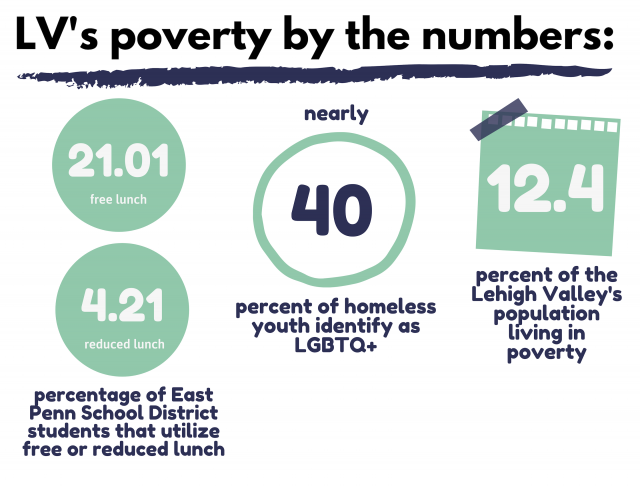

Behind this prosperity, the valley drags behind a poverty rate of 11.1 percent. It also bears the title as the country’s 19th highest concentrated poverty rate among metro areas, according to 24-7 Wall Street’s research from the U.S. Census Bureau. ‘Concentrated poverty’ is defined by neighborhoods with poverty rates above 40 percent.

This area is not necessarily a ‘poor’ region, nonetheless — according to the same 24-7 Wall Street report, the poverty line is slightly higher than the national average. Although, about 15.6 percent of those living below the line dwell in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty, making the Lehigh Valley one of the most “economically segregated” regions in the United States.

However, most of the remaining 84.4 percent of the impoverished population live not just in other inner city neighborhoods, but in rural towns and suburban cul-de-sacs — an occurrence creeping to commonplace even within the affluent districts in Lehigh County. Robinson, alongside 25 percent of his other peers in the East Penn School District, receive free or reduced lunch on a daily basis. This is usually the first indication of decline in a school district’s economic status, one becoming increasingly prevalent in EPSD.

“We’ve seen somewhat of an increase [of students living in poverty] based upon changes in economic status in the United States, whether it’s an economic downturn or recession,” said Thomas Mirabella, Director of Student Services for EPSD.

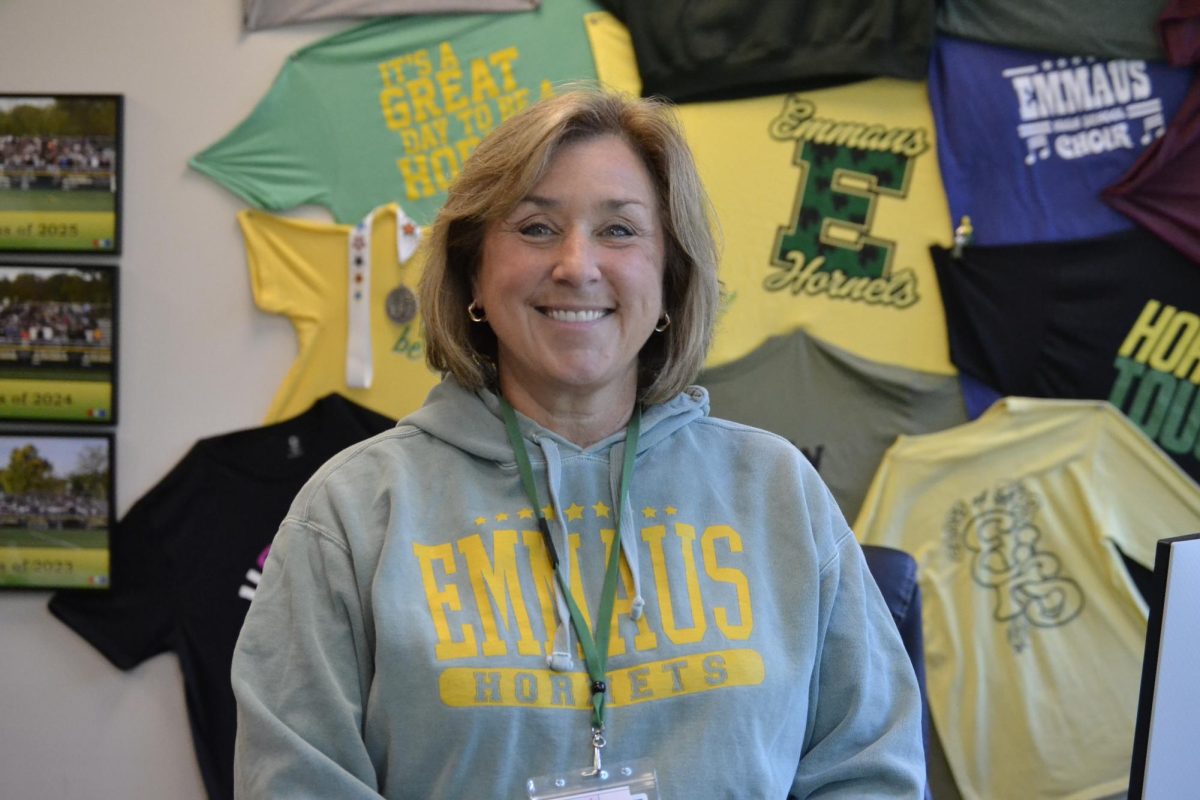

Throughout his 10 years in the position, Mirabella has overseen a variety of students’ housing and economic situations. Whether it be refugees of recent hurricanes, house fire victims, or children of unemployed parents, the district has become no stranger to any circumstances. When Mirabella meets with the district’s home and school visitor, Karla Matamoros, he sees an average of 20 or so cases, or students, from approximately 10 families each month.

During this past September, Matamoros dealt with 28 cases, the “most [she] had seen in a while.” She traces the source of this uptick to increasing cost of living and rent within the district, despite wages from jobs remaining constant.

At EHS, just over 21 percent of students receive free lunch, and 4 percent utilize reduced lunch during the 2019-2020 school year. Students who qualify for free or reduced lunch either are foster children, already receive food stamps, or fall into a qualified income threshold based upon the number of people in a certain household, which is updated for every school year. On top of this, the population of students utilizing this service “are entirely self-proclaimed,” according to Mirabella, meaning that there are more students who qualify, but chose not to apply for the program.

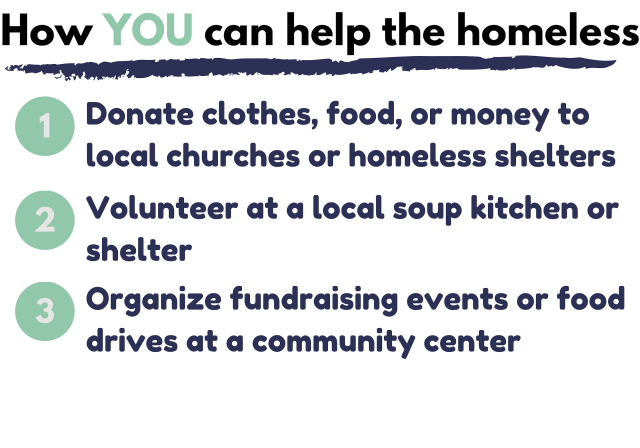

On behalf of the district, volunteers for the Angel Network will help students in need by organizing food, clothing, and school supply donations, along with Quality of Life programs, encompassing any leisure item from homecoming and prom tickets to holiday gifts.

Claudia Murray, advisor of EHS’ Red Cross Club, recalls the Angel Network’s touch of magic to one student in EHS.

“They mostly deal with kids already living in shelters,” Murray said. “But there was one kid living in a park last year because his mom had just died, so the counselors and adult volunteers involved with that specifically dealt with him and helped him through that tragedy.”

Murray, on behalf of the Red Cross Club, is unable to directly help homeless students in EPSD because of The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), which protects a student’s school record from being obtained by a third party. Because of this, Murray’s club will often work anonymously with the Angel Network.

Although the typical Emmaus student has dipped his or her toes in the likes of Key Club or Habitat for Humanity, two popular community service clubs like Red Cross Club, very few have taken the individual initiative to directly help the less fortunate.

Freshman Maitri Nemani, however, prepares home-cooked meals every other week for the local homeless, in contrast to their typical canned food cuisine. She recalls a touching story from one of the people she served — one that makes the two years she has spent servicing the homeless worth to continue for a lifetime.

“There was this one man who was born in New York City, and his parents abandoned him when he was four,” Nemani said. “He then got adopted, but when he came here when he was 18, he was struggling to get a job when we saw him. At the time, he was living in a tent on the side of the road.”

Based on her contributions, she said, “it’s nice to treat them to real food once in a while.”

“It makes me happy because when they leave, they always have a big smile on their face that you couldn’t see before,” Nemani said.

Despite the increasing number of families living in poverty within the district, Matamoros believes her recent casework has been a source of inspiration to the future of East Penn.

“We’ve been very lucky that a lot of the families we have helped have grown out of poverty and continues to live on their own,” Matamoros said. “It’s been refreshing to see.”

LGBTQ+ Youth

She was a natural artist, a natural writer, and a natural helper: Chloe Cole-Wilson, the program coordinator of the Lehigh Valley’s Project Silk, which services homeless or neglected LGBTQ+ youth ages 14-29, combined each of her talents into a career, which she considers a “lifestyle.”

Her job comprises of one-on-one, personal interactions with clients, supervision on each of their situations, and educating youth on their sexual health — overall, she helps kids who, based on their sexual identity, were either forced out of their homes or no longer get along with their family. With a focus on LGBTQ+ youth of color, she hopes to represent various populations she feels is often neglected by most of the valley’s homeless shelters.

Project Silk is a subdivision of youth homeless program Valley Youth House, meaning it often works alongside its fellow divisions to best serve its clients. The Youth House’s Synergy Project, for example, specifically locates street-level, couch-surfing, or house-hopping homeless teens and provides them with shelter and support. Cole-Wilson reports nearly 40 percent of youth off the streets identifying as LGBTQ+, so she is often referred to kids in need of support.

“We try, if we have the funds for it, get identification, in the form of a birth certificate or social security card, for these youth,” Cole-Wilson said. “And that makes a huge difference for kids who are 18 or 19 years old, and can’t get hired or get a job because they don’t have ID. That’s the cycle — they don’t have this one key, which allows them to get a job, and therefore they can’t pay for a house, and they become street-level homeless.”

Even if the program has its limits, such as being unable to provide housing for clients, Cole-Wilson will overstep these frustrating boundaries and helps her youth to the best of her ability.

“Sometimes we have clients that say, ‘I need to be here. I need to be with like-minded people to get through my every day,’ so then they’ll use this space for years and years to come,” Cole-Wilson said. “Without this space, we can’t have supportive services. Without this space, we can’t do case management. Without this space, youth can’t create a safe space and satisfy their social needs. They just need it to get through … life.”

Although she believes it is her life’s work to continue to help youth through one of the darkest hours of their lives, Cole-Wilson recalls on a career-defining case that made her job even more meaningful — all beginning at her poetry and arts studio, while directing a show called ‘Out.’

“During that experience, I had a client that was experiencing street-level homelessness, so that was really hard for her. She was staying at friends’ houses, staying in her car,” Cole-Wilson said. “She began talking about stripping, and not saying sex work isn’t reputable, because it is, but she was doing it only for convenience and not because she actually wanted to. But we got her to the point where we could build up her resume, she began to be a part of the show, and she ended up in a one room shelter on campus with all of her progress. All I had to do is give her the resources. For example, I would give her a phone number to call, and I thought, ‘this could change your whole life.’ We were able to work together, so now she’s about to graduate from college.”

Efforts to Help the Homeless

Although volunteer work and donations through churches, community centers, or homeless shelters are some of the most obvious options for serving the less fortunate, Cole-Wilson believes some of the best support comes through compassion.

“People think that you need to give a person all this money in order to effectively serve them, when in reality, guidance is the service that will make a difference in a person’s life,” Cole-Wilson said. “So for one of my clients, it was calling her, checking up on her, making sure she was making progressions, because she never had that from her parents in her life.”

Christmas — once considered street-level homeless — strongly agrees.

“Just because a person is homeless, doesn’t mean they’re helpless,” Christmas said. “Not every person on the street you pass by needs money. Maybe just a smile. A smile can take you a long way.”

Matamoros created a program called Neighbors Helping Neighbors in 2013, in order to give members of the community the opportunity to pitch-in money to rent an apartment for a family in need. After helping only six families in the past nine years, she believes that even the slightest form of assistance to the less fortunate will make an impact.

“Even if we can’t help every family in the district from experiencing their hardships, it’s the thought that counts, it’s the effort to make even one person’s life easier that counts,” Matamoros said.

Robert Robinson’s name was changed for privacy.