Self-medication: When substance abuse and mental health collide

May 23, 2021

Emmaus senior Cole Smith first encountered drugs in a social setting, mostly smoking marijuana in a recreational manner with friends.

As time went on, they would socialize with the sole purpose of getting high.

In addition to the social expectation to smoke, Smith endured stress as a result of his home life, as well as mental health issues. He recalls coming home to a “disappointed” father, and following his parents’ split, he felt unwelcome. Smith found relief in smoking weed on his own as a way to self-medicate, rather than just getting stoned.

“It was just like a mood changer for me, because I knew when [weed] was there, I was always in a better mood,” he said. “That’s why I realized it started becoming a problem. I was doing it like every day. You know when, when I didn’t have it, I felt alone.”

Smith also used marijuana to “calm down” his anxieties and allow him to be in a better headspace rather than wrapped in his thoughts. Smoking weed was a way for Smith to get out of his own head and allow him to relax. There would be times when he used so he had a reason to simply stay in bed and watch TV without a “care in the world.”

ΔΔΔ

Self-medication — whether it be over-the-counter Tylenol for a headache or marijuana to escape family conflicts — is the decision to use medicine without a doctor’s prescription in order to soothe a physical or psychological problem. Nearly 70 percent of high school seniors have drunk alcohol at least once, and half will have tried an illicit drug, according to the Centers for Disease Control; twenty percent will have used a drug outside of its prescribed purpose.

“Oftentimes, what we find is students that have untreated mental health issues are trying to self-soothe,” said Danielle Walsh, the Student Assistance Program coordinator at EHS. “So they’ll be using substances in order to mask whatever those symptoms are. So if a child has depression, they might be using a stimulant in order to mask the depressive symptoms.”

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a prominent finding among the medical community was a particular rise in mental health issues among adolescents. Mental health claims skyrocketed over 100 percent in April 2020 compared to April 2019, according to a study published by Fair Health earlier this year.

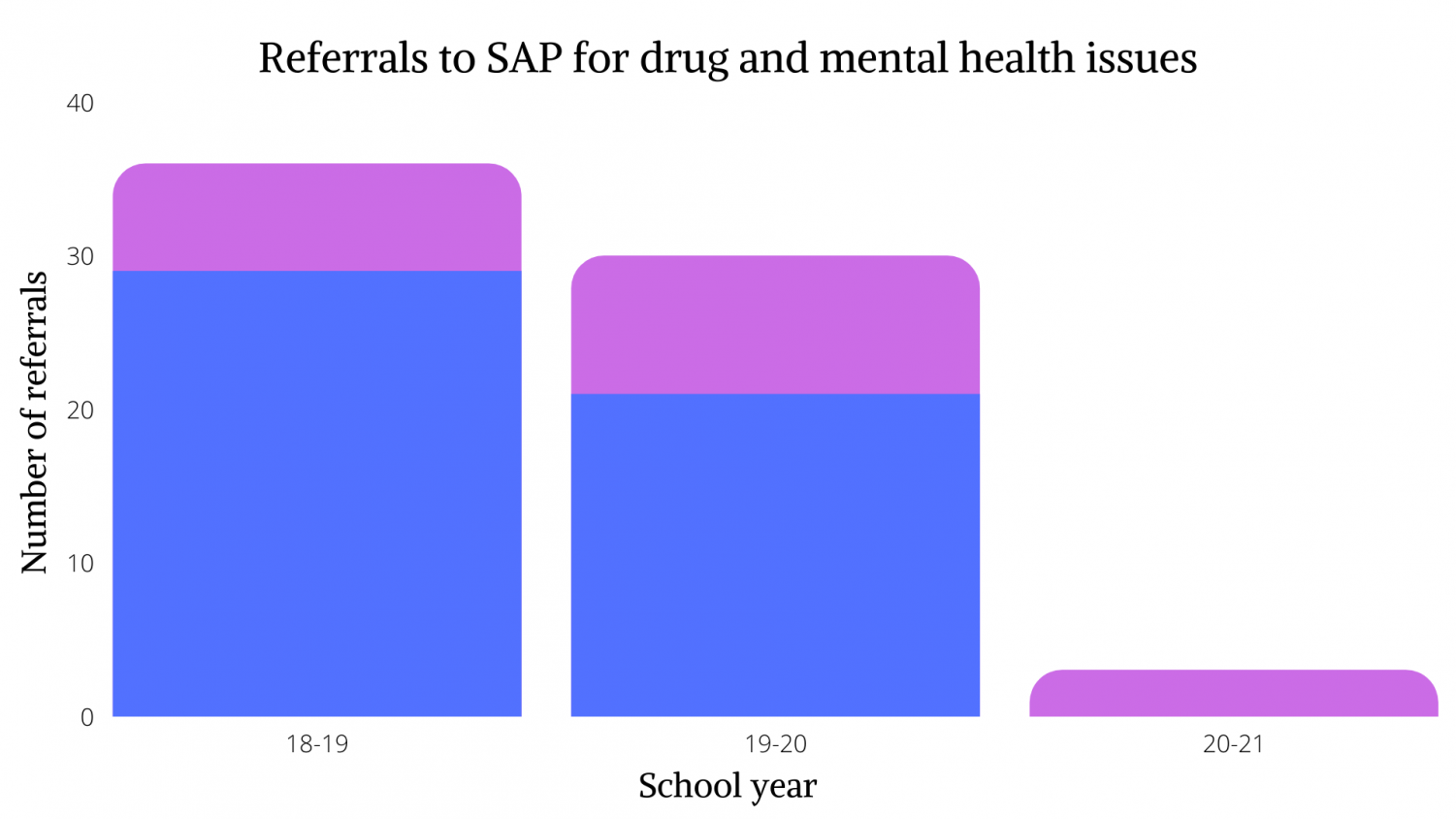

The Student Assistance Program (SAP) is a Pennsylvania statewide resource for schools to identify, assess, and recommend a course of treatment for students struggling in school. Common categories that define the students’ main reason for the referral include attendance affairs and academic struggles, while others deal with family stressors, mental health problems, and drug dependency. According to Dr. Thomas Mirabella, the Director of Student Services for the East Penn School District, the high school typically receives between 10 and 13 referrals per school year with the “primary reason” of the referral being “suspected drug and alcohol issues.” Overall, EHS handles around 130 cases in a normal school year.

However, according to Walsh, the 2020-2021 academic year has not been typical. As of March of this year, she has only gotten 24 referrals, with none being associated with drug and alcohol issues.

“This is unusual, this is not how it normally works,” Walsh said. “We get 24 in the first like two to three weeks. Not all year.”

The bulk of referrals for this school year stemmed from academic concerns, which is a broad term to describe a student’s ability to progress towards the next grade level. Although test performances and missing assignments are an obvious indication of a student’s academic status, it is clear to Walsh that there is an invisible population of students that are not receiving referrals — especially those struggling with self-medication.

“If you’re here in class and you’re smelling [like] tobacco, we’re gonna notice that. If you’re here in class and you smell like a skunk because you’re smoking pot, we’re gonna know that,” she said. “But if you’re at home, we have no way to really decipher that, so the only way to tell if somebody is using in the cyber world is to pay attention to what’s going on around that student.”

ΔΔΔ

With time, Smith and his friends would only hang out if they were going to smoke marijuana, and it came to the point where Smith felt uncomfortable socializing without being high.

“And then it just became like one of those things, it’s like, I can’t go outside today and hang out with friends because I didn’t have [marijuana],” Smith said. “It was just something that I did, like, every single time we hung out.”

Eventually, marijuana was no longer fulfilling his desired level of escape through drugs. Smith started searching for a “better experience” and found himself using psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin, sometimes referred to as ‘shrooms.’

Smith noticed he had created a sort of dependency on marijuana. He couldn’t have fun with friends while he was sober. He felt alone without the luxury of being high. If he wasn’t smoking, it was harder to go about his day.

“…I felt like it was because, like, if I didn’t have [marijuana], my friends didn’t want to hang out with me. Or, like, spend time with me. I felt like nothing was as fun without it,” he said.

ΔΔΔ

John Jezick visited Emmaus High School health classes during the 2019-2020 school year to discuss his previous battles with addiction. Now working with law enforcement to respond to overdose calls to encourage people to take the step towards rehab, his path to becoming an addict in recovery has been nothing short of a never-ending journey. He spent 17 years in prison, and abused nearly his entire lifetime.

“In the beginning it’s occasional usage, like maybe a few times at football games. When I played for Central Catholic [High School], we would get together afterwards and smoke a few joints. Then, that Friday night turns into Sunday night before school. You start to abuse it. Then when you pass the abuse level, you need it to function,” Jezick said. “I remember waking up after a keg party on a Monday night and I was shaking. I went from drinking and smoking, to getting this scar on my arm from shooting drugs.”

Now, amid the pandemic, Wendy Texter, SAP liaison and representative from the Center for Humanistic Change, worries that substance abuse reports will go through the roof the moment students begin to return in-person. As students are able to mask their personal problems behind a computer screen in the current remote setting, self-medication cases will simply fester until they will be able to be properly addressed.

“The mental health concern is pretty high for me right now,” Texter said. “I’m afraid for kids coming back.”

And as Pennsylvania prepares to lift all COVID-19 restrictions during Memorial Day weekend, the likelihood of students returning to in-person school during the next school year is rising. Texter believes this could potentially lead to an overwhelming influx of students needing SAP services.

Substance abuse — as it begins to tread a fine line between recreational use to dependency — is oftentimes the result of an underlying problem. And before Jezick could confront the reasons behind his initial use in high school, his experimentation in drugs became debilitating.

“Do you think when I was in school I thought I was going to introduce myself as, ‘Hi, I’m John, and I’m an addict?’” he asked students in his audience.

ΔΔΔ

At the peak of his use, Smith didn’t think he had an addiction or used it in a way to relieve his stress. But after noticing his usage becoming frequent to the point of smoking every day, he accepted that he was deflecting his problems through the use of marijuana.

“It just seemed so much easier for me to just sit there, ignore my problem and just be high,” Smith said.

After talking with his therapist about how to become sober, Smith decided to quit smoking weed entirely.

“I was able to like, hang out with people, and not have to do it at all. I went cold turkey but it was kinda in moderation. I was, I was able to go like a month or two without it,” he said. “The most I went was like four months. And when I was brought up, I was able to say no– even when pressured.”

ΔΔΔ

Breaking a bad habit is not easy in any circumstance, but it becomes even harder when an illicit substance is added into the equation. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the rate of relapse for those seeking to quit substance abuse is between 40 and 60 percent, which echoes relapse rates of other chronic illnesses like high blood pressure.

Recovery from drug addiction is very possible, however. The NIDA reports that about 10 percent of Americans over the age of 18 are in recovery from some form of substance abuse. This is made achievable by programs such as Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous, along with the 14,500 or more specialized drug treatment facilities for those with substance use disorders in the United States.

The most important step, says Jezick, is education. “Get them away from the substance, get them in rehab, or get them on medically assisted treatment,” he says.

While it may be difficult for many to recognize the severity of their problem — the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health revealed that only 5.7 percent of people that required, but did not receive treatment for substance abuse felt that they needed it — it’s important to curb drug abuse as soon as it’s noticed, especially in teens. The human brain is not fully developed until a person is in their mid-20s, and because chronic drug use can “alter key brain areas necessary for function and self-control,” says the NIDA, continuing use makes it increasingly more difficult for someone who is addicted to stop.

Overall, as students begin returning to school, vigilance is necessary to remedy the issues of those who might be falling through the cracks — whether it be due to a bad living situation, mental health issues, or anything else. Substance abuse is one factor of a major crisis in adolescent mental health. If that is truly to be addressed, other systemic and personal issues must be addressed as well, and everyone must work together to spot warning signs.

“I think everyone needs to pay attention to each other,” says Texter. “I think parents need to be aware of what’s going on with their kids…friends need to watch out for their friends, and also kids need to be able to be honest with themselves if they’re struggling, they need to reach out to an adult, or someone in the school who can help them.”

At Emmaus High School, that help can be found using the Safe2Say app or website, calling the anonymous tip line at (1-844-723-2729), or talking to any trusted adult like a teacher or counselor who can guide you in the right direction.

Cole Smith’s name has been changed for privacy.