Bridging the gap: Local teachers examine lack of diversity in education

June 10, 2021

“What’s happening is not fair, and it will never be justified,” Emmaus freshman Elizabeth “Tami” Adesanya says. “That’s why it’s my job to speak for people who are scared to speak.”

In East Penn, a predominantly white school district, Adesanya is one of two dozen students who strive for change and action to create an environment where people of color feel welcomed, safe, and heard. As a member of EHS’ first Black Student Union and the treasurer of Students Organizing Against Racism, or SOAR, she is passionate about ensuring that young POC like herself won’t go through the same experiences that she did.

“To think about these kindergarteners, first graders, all these young people who might have to go through the same things I went through?” Adesanya says. “I can’t let that happen. It’s my job to stop that from happening.”

Part of their fight, and the larger fight of civil rights organizations across the nation, is raising awareness on the lack of teachers of color in the modern education system. White teachers outnumber teachers of color at a disproportionate rate in America, despite the rapidly growing number of POC attending schools. This issue can be seen, as well, at EHS, where 529 students of color attend; in turn, the school employs one teacher of color. This statistic does not include administrators, staff, or teachers who identify as Latinx.

According to Adesanya, having educators of color in schools is a crucial first step to a path of equity, openness, and inspiration for all students, and importantly, students of color.

“There are [almost] no teachers who are people of color, so who am I looking up to?” Adesanya questions. “I don’t have any real inspiration.”

Teachers of color are proven to have higher expectations for students of color, confront issues of racism, serve as advocates and cultural brokers, and build trusting and valuable relationships with students who share the same cultural background, according to the State of Racial Diversity in the Educator Workforce. Teachers of color stand as positive role models, break down barriers of stereotypes and hate, and better prepare students to live in a multiracial society outside of school.

This is true, even in the Lehigh Valley — the Allentown branch of the NAACP continues to emphasize the importance of diversity in school staff.

“There are a number of studies confirming students of color are positively impacted by seeing teachers and administrators of color,” the NAACP explains in a statement to The Stinger. “Children from all backgrounds benefit as they see people who reflect the cultural diversity they will encounter as adults.”

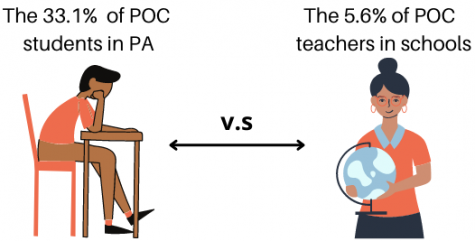

While the impact teachers of color leave on students of color is crucial and groundbreaking, Pennsylvania specifically suffers a great amount without them. The gap between students of color in the state, 33.1 percent, and teachers of color, 5.6 percent, is one of the most disparate in the country, according to Research for Action. And as of 2020, more than half of PA’s schools only employed white teachers.

“While students of color are expected to make up 56 percent of the student population by 2024, the elementary and secondary educator workforce is still overwhelmingly white,” the State of Racial Diversity reports.

Reflecting upon Emmaus’ own students of color to teachers of color ratio, EHS assistant principal Greg Annoni believes it is a necessity to counter the widespread lack of racial diversity in schooling staff.

“We absolutely must increase diversity in hiring,” Annoni says. “Students of color who have teachers of color tend to experience academic success. They have less disciplinary infractions and are more likely to graduate.”

As an educator of color himself, Annoni mentions that his experiences and feelings over the years have differed from that of his colleagues. He explains that research shows that teachers of color often feel fear, frustration, and fatigue when placed in a school environment where their minority makes up a very small percentage of the staff.

Spanish teacher Isidro Figueroa, in his experience as a POC, has found that being in that small percentage is unavoidable in the world of education.

“It would be great if we had teachers of every heritage or whatever it might be, whatever community should be represented in the staff,” Figueroa says. “I worked in five different schools and at every school, I’ve been one of a handful of minority teachers.”

Tabitha Rodriguez, another assistant principal at EHS, has used her background being an educator of color as a teachable moment for her students, tending to reflect on the challenges she has faced and bring out the positives.

“Negative experiences … I’m just using, more so, as a teachable moment,” Rodriguez says. “I can turn it around and bridge any gaps, address any misperceptions, and any misunderstandings or anything of that nature.”

Harold Fairclough, the only Emmaus High School coach of color, also believes that a more diverse and shared experience would be beneficial for all.

“It is important to see a person of color in a leadership position,” Fairclough says. “This gives [students of color] a sense of representation. It is equally important for players who are not black or brown to see a man of color in a leadership role. So, often the media portrays black and brown men in a negative light. It is my hope for them to have a positive experience with a person of color.”

Expressed by the few teachers of color at Emmaus, connecting with students of color who share the same cultural background as them is equally vital. Holding a position as an educator or administrator serves as an example for POC, and reminds these students of what they can accomplish and have the potential to be.

Annoni, like many other teachers of color, strives to be a role model for other POC at EHS.

“Diverse learners need to feel as though they’re in a partnership with their teachers,” Annoni says. “Ninety percent of the time, I have this shirt and tie and jacket on because I think it’s important for my students of color to see a positive person of color in that position.”

Proof of the impact teachers have on students of color can be seen in mentoring relationships within the school. Adesanya, for whom it is difficult to find inspiration in a district with a majority white teaching staff, is able to confide in Annoni’s mentorship and his willingness to connect with all students.

This understanding came from their shared background as POC.

“It was so much easier to talk to [Mr. Annoni] because he looks like me,” Adesanya says.

Since students of color find comfort and an outlet in having a diverse teaching or schooling staff, these teachers strive to connect with their POC students in any way they can. Dr. Harrison Bailey, the principal of Liberty High School in center city Bethlehem, describes not only connecting with his students, but the general necessity of diverse staffing in the classroom, as “critical.”

Over his years teaching, he has discovered first-hand the importance of building a relationship with minority students in his schools.

“I’ve been in … numerous places where there wasn’t a high number of minorities in the staff,” Bailey says. “And so when you have that scenario, your students of color tend to look for you as that kind of one person, right, and they connect with you because they need that connection. So, the difference in experience comes down to being in a position where you are connecting with a lot of students who may not connect with many other people in the building.”

Bailey has also experienced moments where he realized the importance of seeing other POC in positions of authority for students of color. Not long after learning he was going to be the new principal of Liberty, a POC mother and her young son approached him while he was competing in the Scottish Highland Games at Celtic Classic. She introduced him, and told her son that Bailey would be his principal once he got to Liberty.

“And for him, seeing I was the only African American out on the field competing that day, kind of invoked [a] feeling of pride in that,” Bailey says. “You know, ‘Wow, if he can do that, [if] he can get out there and do that, I can be successful.’ That was the whole reason I got my doctorate, is to show our students of color that you can do it.”

Rodriguez had a similar experience with a student of color who had been called down to her office during her second week as an administrator. Noticing they were both of Puerto Rican descent, she began speaking with the student in Spanish, asking him questions while he gazed back at her with “amazement.”

The boy asked, “‘Are you really the assistant principal here?’” To which Rodriguez confirmed that she was.

“He tells me, ‘Oh my god, I waited for so long for someone like you to come along,’” Rodriguez says. “That moment I’ll never forget. I get goosebumps. To see someone in a position of authority and to have someone of his background that can speak Spanish with him — he had an absolute look of amazement.”

This influential representation has unbelievably positive outcomes on students of color. However, the experiences of POC within East Penn raise different issues with the state of diversity in the school district.

Adesanya expresses her frustrations with the district regarding the experiences and microaggressions she has gone through as a POC during her middle and high school years; these include being told she could not take an honors class despite meeting all the requirements, peers asking if they could touch her hair, and being called slurs.

“I don’t go up to you asking to touch your hair, so why are you touching mine?” Adesanya asks.

Junior Sydne Clarke, the founder of EHS’ first Black Student Union and President of SOAR, has her own share of experiences with microaggressions.

“The looks I would get from my peers as we were being taught about the Civil Rights Movement or slavery,” Clarke says. “It’s all the little things that add up.”

There comes a moment when enough is enough. With the rise of youth activism across the country, from both groups like SOAR and the increasing presence of social media activism, it becomes clear that a breaking point has been reached. Many youth activists feel that this can go on no longer, and that uncomfortable conversations need to be had and made comfortable to talk about.

EHS is preparing for these conversations via multiple fronts as the school year comes to a close, including through the implementation of their Equity Plan and through the actions of various committees and boards.

“The district as a whole is really taking some steps right now with the Diversity and Inclusion Committee,” Annoni says. “There has been some ongoing work by the district instructional leader team that has some teachers involved, and now they’re taking that work into EHS … elementary schools, and middle schools.”

Along with this new approach to creating a place where POC can feel comfortable, Annoni mentions how the community must “acknowledge and accept that there’s an ongoing growth that has to occur.” Accepting that things need to change, looking inside oneself, and realizing that a precedent has to be set is a vital step toward creating a space where every student feels as though they belong, and are heard just as equally as their peers.

This growth not only needs to start in the classroom and the hallways, but deep in the school curriculum. With a serious lack of education regarding black history and POC cultural backgrounds, how will students of color learn about their culture or the importance of it?

“I’m not trying to be a burden to you,” Adesanya says. “This is something I want to know about: my history, my culture. But I’m not learning that. If I want to learn it I have to do it myself.”

With lackluster coverage of Black History Month, there is virtually zero representation for everybody, not just students of color, to learn and see.

“Black history is vital to the understanding of American history,” Annoni says. “Period.”

Clarke also mentions how she has to use other resources to teach herself about black history, and parts of her culture’s past that are not being actively taught in her history classes.

“For Black History Month, they showed a 2-minute long video on the announcements,” Clarke says. “There was nothing other than that for black history.”

Although Emmaus and other local schools are taking steps toward inclusion within their school environments, it is difficult to achieve this goal fully when many diversity issues lie in the systemic oppression of POC in societal structures. How can schools hire more teachers of color when there is a lack of POC pursuing education? And what can educators do to encourage students of color to take advantage of these paths?

Figuero believes that this lack of interest in education from students of color is inherently tied to the lack of minority teachers.

“It’s a systemic thing,” Figuero says. “…If you have 30 students, and 29 of those students see themselves in someone throughout their day but that one person doesn’t, in this case, minority students may not be as inclined to become educators because maybe they never saw someone that looked like them being educators. So, it’s really difficult. I would like to see a push for that because even in the board meetings and here at school we talk about diversity a lot, but it’s not representative of how much we talk about it, versus how much we do of it.”

Bailey agrees that more action needs to be taken to break this cycle, and argues that local schools should be doing more to encourage students of color to pursue education.

“We don’t do enough,” Bailey says. “Now, that’s a loaded conversation, because there’s a lot of reasons that that is not happening. One is a pool of candidates [that] doesn’t hold what we would consider to be a diverse pool. But then, the question is, why is that? Well, out of what we can control — which, now, isn’t that much, necessarily — but out of what we can control, I think we don’t do a good job of selling education to our students. To say, ‘This is a great profession, this is something that you should want to do.’”

To bridge the disinterest between students of color and careers in education, Bailey has turned to academic leadership seminars. These seminars develop leadership skills in students of color to prompt them to think about their future after high school. Bethlehem has also created an “education pathway” where students can take courses in education, and then matriculate into local colleges looking to diversify. This emphasis on bringing more POC into education is equally as important as hiring more teachers of color, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

Bailey emphasizes that these projects are a “long-term investment.” The Lehigh Valley is not going to see the results from these programs tomorrow, and he asserts that people should not expect to. At the end of the day, the goal is to “create a stream” of “good teachers of color into the profession,” no matter how long that takes.

Additional reporting by Erick De La Rosa and Victoria Bruckler.