This was previously published in our April 2024 issue.

Parties: dancing, drinking, and “living in the moment.” For many high school students, this type of party mentality can seem harmless; trying substances once, surrounded by friends, can seem innocent. However, these choices can become habitual, and what begins as spur-of-the- moment decisions and harmless teenage fun can spiral into something more dangerous.

When these behaviors begin to bleed into other aspects of students’ lives, it begs the question: what role do schools — including EHS — play in combating party culture? The widespread participation of teenagers in unsafe party behaviors and the subsequent aftershocks and devastation.

Substance use as a teenager has a way of following people throughout life. According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), the early initiation age for drinking is typically 15 years old. This early initiation is associated with the development of an alcohol use disorder later in life.

The younger someone gets involved in drinking and substance use, the more disastrous the outcome can be. The CDC also states that students who begin using alcohol regularly at ages 12-14 have lower educational achievement in later years and that the neurotoxin exposure associated with alcohol and substance use during adolescence can harm brain development, with “even minor changes in neurodevelopmental trajectories affecting a range of cognitive, emotional, and social functioning.”

Two members of the Emmaus chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Teresa and Tony — who wish to remain anonymous for privacy reasons — wanted to tell their stories of turmoil through the years.

Teresa shared her own experience and how drinking affected her in high school.

“I was a three-sport athlete. I ended up being captain of my team. I always did very well academically, and I had a lot of friends, but I kind of just [drank] because that’s what everyone else was doing,” Teresa said. “But for me, I always sort of took it like a step further. I always ended up blacking out that night. The way I was drinking was really problematic.”

Alcohol slowly took over Teresa’s life, but many of her friends, who were also athletes, struggled at her school with these issues.

“It actually hurts both parties a lot because I don’t think either really gets help. When I was in high school, I was sort of one of those students that, you know, was involved and did all the things, and then I ended up going to college, but I still ended up with this [addiction]. I still ended up in the same place. I still ended up with those same sorts of problems, and they’re still ignored by all sorts of students. So irregardless [sic] of if you’re involved academically or not, it’s not treating the root of the issue.”

The issue was widespread, not just at Teresa’s school but also at EHS. As an Emmaus alumni, Tony voiced his concerns with the school’s failure to address these problems properly for years.

“I was 14, and I started hanging out with the kids that were kind of the outcast kids, so we found something to keep ourselves busy,” Tony recalled. “I started smoking weed and drinking a little bit at 14, and at 15, I was using coke regularly [and] on LSD at 16.”

Being perceived as an outcast pushed him towards using drugs more, according to Tony, in part coming from “a level of just wanting to be accepted.” Even then, he was far from alone in his experience; he described how students from all walks of life were involved in these same activities.

“I was in Saturday morning detention [with] our star soccer player. We ended up doing lines in the bathroom together,” Tony said. He continued, describing how inequity between students makes the problem much worse. “It was clear to me that if you were a star athlete, or if you [had] good grades, anything else got ignored because you were a good light for the school. You were somebody that the school was proud of.”

Tony began sharing a personal experience from his senior year at EHS, where he got into a brief confrontation between classes.

“I hit him [another student] once, and I turned myself into the main office right after it happened, and they tried to expel me. We went to the hearing, and my mom defended me and said, ‘You have kids that get in a fight every day here in the school and then skip school right after the fight happens, and you don’t see them for two or three days. They don’t get put up for an expulsion hearing, but my son hit somebody once and turned himself in, and this is the result. He’s never caused a problem before,” Tony said. “The reality was that they tried to single me out and say that ‘oh, well, he’s on drugs, and he has a drug problem,’ [But] I’m not the only one — and that was the point that was made in that meeting with the administration. [Yet] you [EHS] have a major drug problem here, and you’re not looking into it at all.”

Tony voiced that EHS had a lack of support for students struggling with substance abuse, and while outside programs existed at Emmaus, the school didn’t make them accessible enough.

“There was a Youth Recovery Program in Emmaus called Vision, and anybody that was involved with juvenile probation for Emmaus … had to go through this program for an evaluation,” Tony said. “So it was a known thing by the Emmaus Police Department that Emmaus High School had a drug problem, but Emmaus High School refused to admit that it had a drug problem. They just denied it vehemently.”

This does not mean, however, that there are no steps forward to help students.

“A solution is the Student Assistance Program. Or a Youth Recovery Program,” Tony said. “The Youth Recovery Program, Vision, that I was in was awesome because when you’re in high school and you might be stumbling down the wrong road with drugs and alcohol, you need an out somewhere.”

He described how helpful being in this program was — how being around other similar teenagers inspired him and showed him that if they could stay sober, he could too. Tony claims the rapport and trust built between them and the advisors were essential in his journey.

Other programs are still available in Emmaus today. “Reach LV” (Reach Lehigh Valley), the current Youth Recovery Program in Emmaus, offers such support.

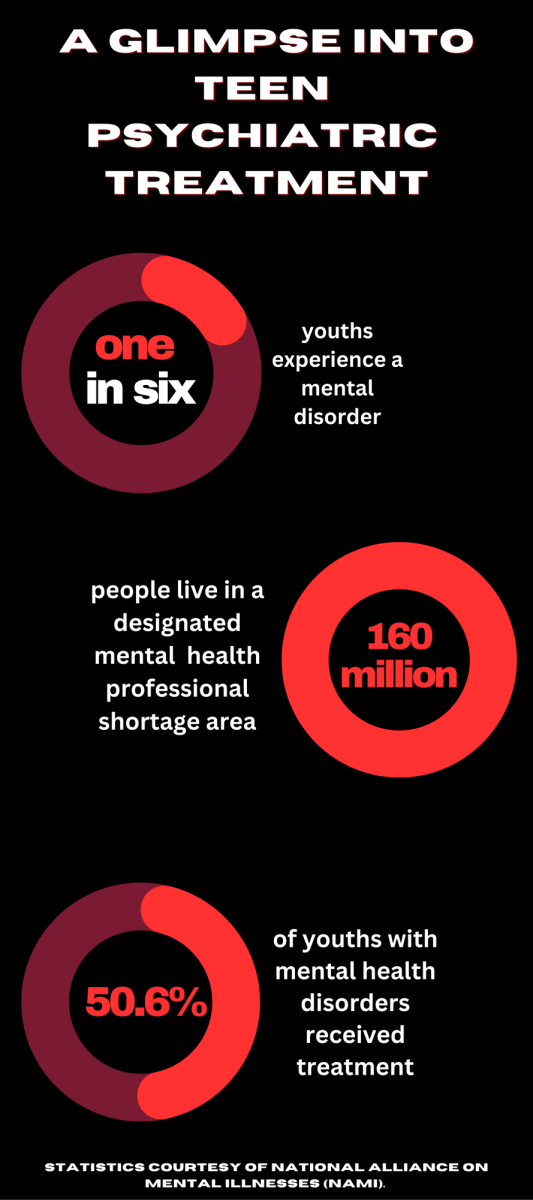

Similarly to Reach LV, Emmaus offers support through the Student Assistance Program, also known as SAP. SAP is a program meant to target issues that “pose as a barrier to student success,” including, but not limited to, alcohol, tobacco, nicotine, marijuana, and student mental health. At EHS, SAP is a teacher-run organization that works with students to minimize the damage to a student’s education that external factors can cause while also seeking treatment and help for struggling teens.

Brian Harkness, a SAP team member and science teacher at EHS, shared some information regarding the SAP team’s work.

“We receive referrals from teachers, [and] other adults who work with students in the school…After our weekly meetings with one another and counselors on the team, we decide if the concern warrants a contact home to offer services,” Harkness said.

He explains the various help pathways that SAP offers at EHS.

“There are three levels of service we can offer: [the] first level is to meet with just us, [the] second level is to meet a Community-In-Schools counselor and a group of students with similar needs, and lastly, parents may opt to have their child evaluated by an outside counselor that does the interview at the school but then gives those suggestions to the family.”

Even with a multitude of different support systems and programs set in place, “party culture” and substance abuse are still significant problems within schools across the country.

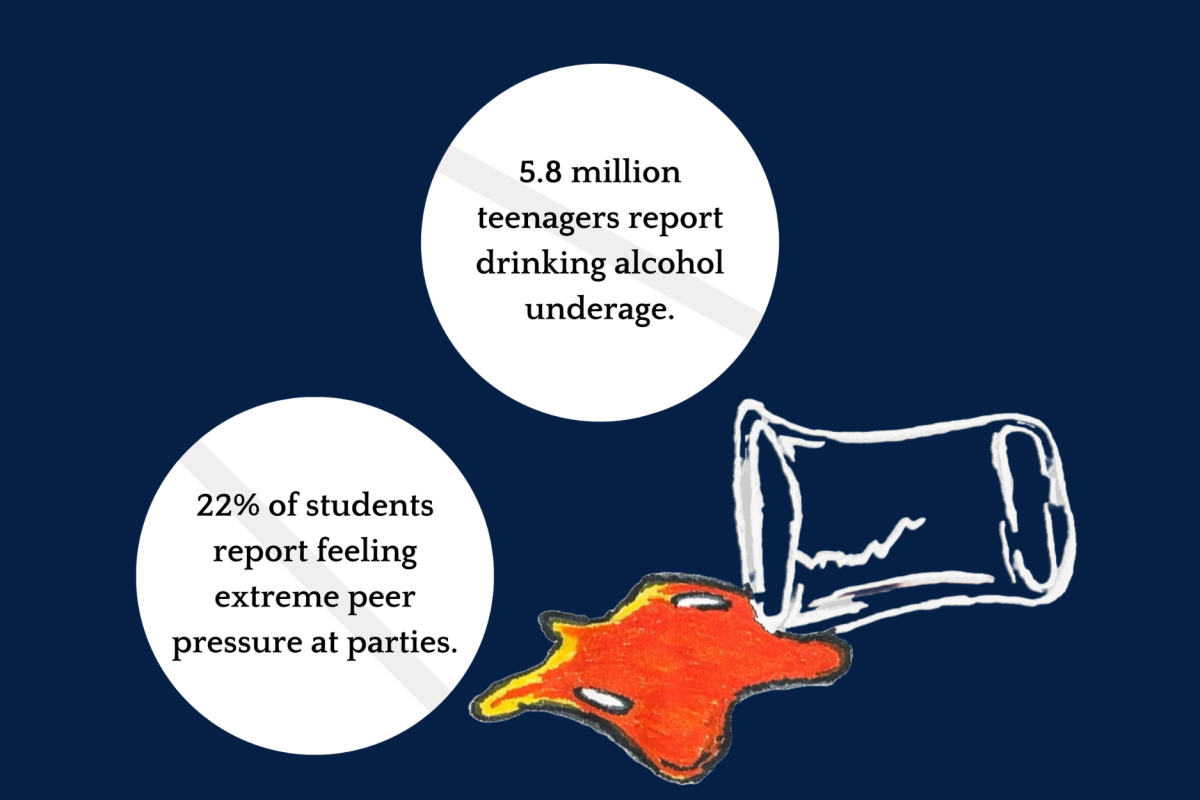

According to a study done by the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics (NCDAS), 84 percent of teens report having used marijuana, and 62 percent of teenagers in 12th grade have reported they abused alcohol at least once.

While it often starts as a way to relax or have a fun time with some friends, teenagers are at the highest risk of developing addiction to substances due to their underdeveloped brains.

“Party culture is an escape mechanism for students who probably bit off more than they can chew, and so whether they’re being forced to by society, parents or whatever, and it’s a way of trying to cope with the excess stress,” Harkness said.

Even still, integrating recovery programs into schools can be tricky—one is bound to receive some pushback. Incorporating these kinds of programs and solutions isn’t “pretty.” Being such a sensitive and influential topic, it can be challenging for schools to address.

Nevertheless, addiction and substance abuse cannot continue to be neglected. What makes the issue so complex is the same thing that makes it necessary to address.

“You’re very soon going to be adults and have to make adult decisions. It starts in high school; learning how to make those adult decisions, with the help and guidance of parents and teachers and school administrators and your friends.”

Drugs are certainly not the most straightforward topic to address, but that does not mean they can be slid under a table, hidden away. If left unattended, problems evolve — they do not disappear. They are like weeds yet to be picked.

Tony wishes to prove to the school district that while many within the school may wish to live in a reality where drugs only affect a particular, distant group of people, both Tony and Teresa point out they do not.

“In the recovery community, there’s all sorts of people. [Addiction] is a thing that does not discriminate against anyone,” Teresa said. “It doesn’t discriminate when you’re an adult, and it doesn’t discriminate when you’re a teenager either.”