“I’ve only been here for two months, and there’s so much going on, and it’s kind of scary,” Preity Banque, a sophomore multilingual learner student at Emmaus High School, said, gesturing at the crowded room she sat in.

This can be true for any new student, but it’s especially true for multilingual students who come to the school with little knowledge of the English language. This has only become more prevalent with the recent decision to merge all but one English Language Develop class with CP English classes.

For years, the English as a Second Language (ESL) program, now known as English Language Development (ELD), has been an essential part of integrating students who speak little to no English into highschool.

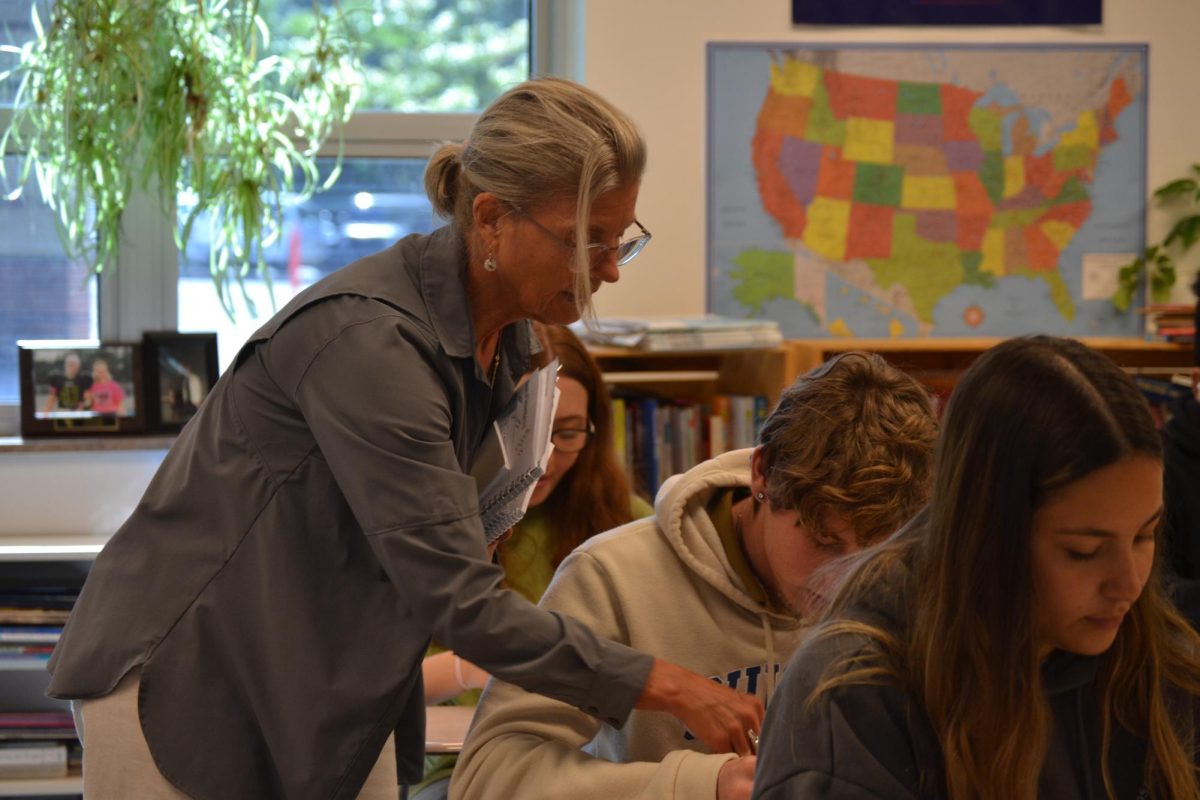

ELD teacher Tammy Kita has worked to make her room a safe space for these students, providing an environment conducive to this daunting task.

“It’s really important to me that these kids, who might be a little more timid in other classes, can have this place they’re comfortable in,” Kita said.

However, this norm was recently overturned — starting this year, all students who had been enrolled in ELD were instead integrated into College Prep (CP) English classes.

Following an audit by Montgomery Intermediate Unit in January 2024, the school was informed that it was not meeting state requirements by failing to enroll ELD students in on-level English classes. To rectify the issue, the school administration removed all English learners from ELD classes — with the exception of new students speaking no English — and put them in CP English classes.

“We have a duty by the law and a responsibility to the students to ensure that we’re providing them what they’re entitled to in terms of an educational experience,” said Dr. Jessica Thacher, East Penn supervisor of secondary education, said.

Many people strongly believe that ELD should have remained separate from CP English.

“I was joking with one of the math teachers, and I gave him a bilingual dictionary with Chinese and English, and I said, ‘Oh, now you can take the Keystone in Chinese!’” Recollected Kita. “It was a joke, obviously, but it kind of shows the unrealistic standard we’re holding them to.”

English class also introduces complex vocabulary meant to challenge native speakers. An individual who is just learning English may struggle to keep up with the curriculum to a greater extent.

“They move so fast,” another multilingual learner, senior Shantel Vargas said. “I’m always late [answering] because before I can answer, I have to translate.”

According to Kita, many ELD students have to rely on Google Translate to keep up in the class. While the tool can be useful

for allowing students to quickly translate what the teacher is saying, problems arise from this too. Students report that the lag often found in Google Translate’s audio function can cause them to fall behind, mistranslations are all too common, and some important messages are lost in translation.

Another perceived problem with this new policy is the loss of a community caused by the dismantling of traditional ELD classes. Many non-English speaking students felt at home in ELD, as they might have connected with other students in an environment where they won’t be judged for their lack of knowledge in English.

Another issue that arose was the question of how such an ambitious task as integrating two separate English courses together would be accomplished.

“We obviously wanted to start on the changes right away, but at that time it was the middle of the school year, and we couldn’t implement those policies at that point,” Thacher said. “But we absolutely had to go into the school year ready to make this shift.”

Instead, they began their efforts over the summer, focusing mostly on professional development for both ELD supports and English teachers integrating ELD students into their class.

When the school year started, there were immediate challenges facing both students and teachers due to this change.

“At first, this teacher assigned the kids a dystopian text, and I was like ‘oh my gosh, these students that don’t really know English are being asked to read this dystopian short story, how is this gonna work?’” Kita said.

However, this strategy ended up working well. Kita was able to supply them with both simplified versions of the text and a version of the original text in their first language. Kita and her students would meet and take notes ahead of time and help make sure the students comprehended the general themes before moving onto more detailed analysis. Kita believes this first test to have been a success. She also reports that the English teachers have been crucial in this effort.

“I’ve been communicating with everyone in the English department pretty much constantly,” she said. “I’m helping them support these kids in any way they can, and they’re doing awesome.”

There are benefits to these changes too. As the intermediate unit stated, it is important for these students to be exposed to the standard learning for their grades and connect with the larger population of EHS.

Despite these helpful aspects, the ELD program is having trouble finding enough teachers to support this demanding program.

“We don’t have the number of teachers that we would want to have to make it run seamlessly, so we’re doing the best we can with what we have, and I think that’s been a barrier,” Thacher said.

In spite of the issues arising from these changes, Kita believes it will ultimately have a positive effect on the school.

“It’s like I say to my Global Citizens Club,” Kita says, “In the end, we’re all just a part of the big wide world.”