The first time I ever felt insecure was in elementary school when a big, red, Jupiterian spot appeared on my cheek. It looked a little like someone had pricked my face with a needle, and blood was pooling in one drop. Connecting to it there were faint red lines — like a little red web with one big spider in the middle.

When I first recognized it, I was indifferent to the mark. Child-me may have raised an eyebrow, but at the end of the day, the mark would not affect my ability to play Wii Sports Resort or win a game of grounders on the school playground. To me, it was just a feature, not a concern.

To everyone else, the mark was an issue. What was it? Was it a health concern? Did I need to see a doctor? Why was it so ugly?

And so to the doctor I went. They determined what it was quickly enough — it was a spider angioma, it was harmless, and they could get rid of it. Just one trip to the dermatologist and they could zap it away — one flash and a bag of frozen peas held to my cheek was all it would take to get rid of it and bring my face back to its previous state. The verdict was quick and final: I would undergo the big zap get the mark wiped from my face for good.

This is when I finally realized how important the spider angioma really was. To others, it was ugly enough to justify taking a laser to my face. The spot may have been harmless to my health, but clearly, it was harmful to my appearance.

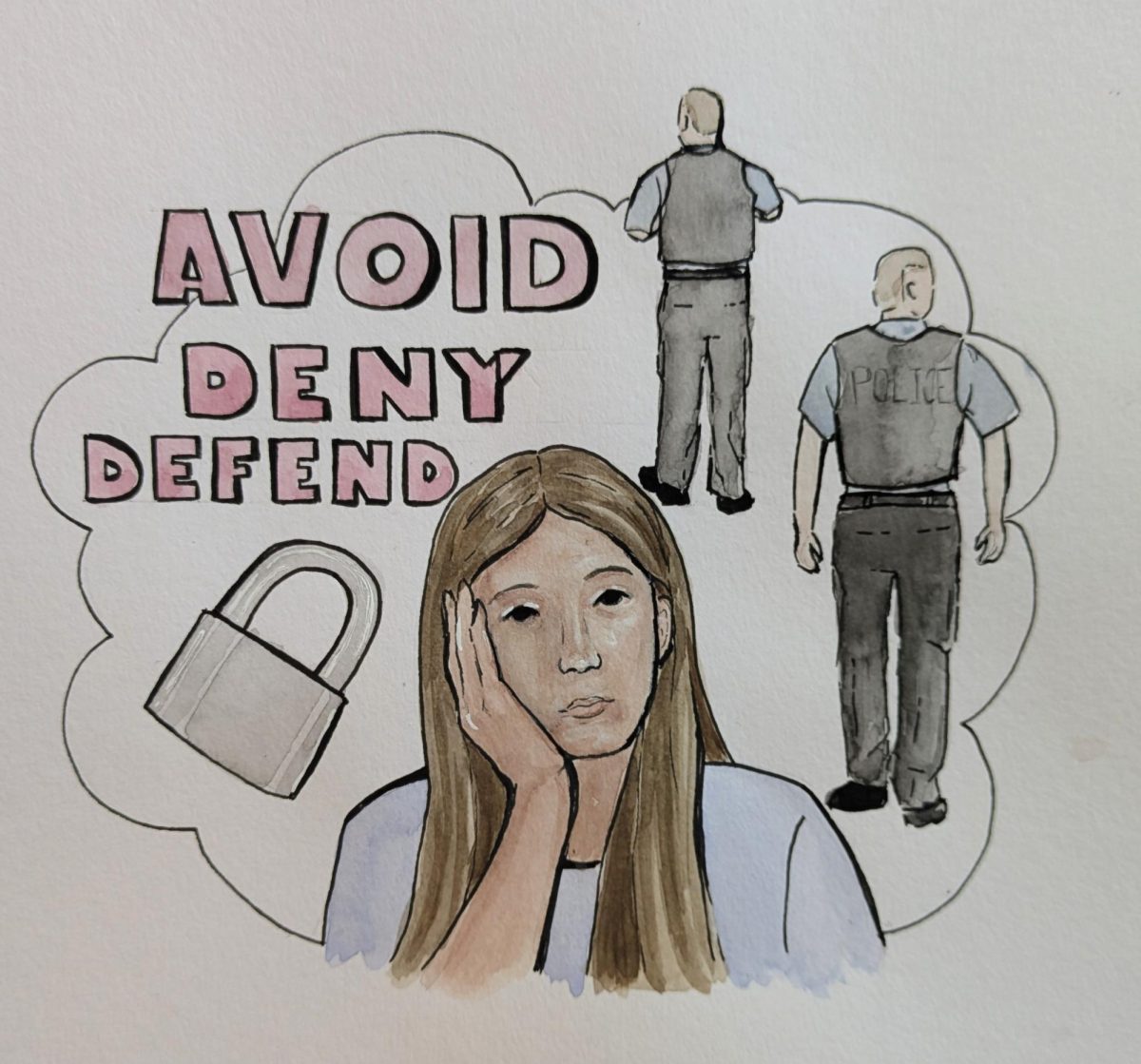

When the day finally came to get it removed, I was a bundle of nerves. The big zap was all I could think about. The nurses beforehand had explained it wouldn’t hurt: it would only feel like snapping a rubber band on my skin.

I finally met the doctor on the day of the visit and, rather quickly, we both realized the truth: he didn’t want to zap me, and I didn’t want to get zapped. It was no noble thing — I was simply younger than any patient he had ever had, and he didn’t feel comfortable performing the procedure on me, especially when I was already so anxious.

We decided to forgo the treatment, and instead, I would just return home and try to forget the whole ordeal. The spider angioma stayed, and life went on. The only difference: now, I was hyper aware of the mark. Now, when I looked in the mirror I saw it glaring back at me. In school, I felt like everyone saw the mark, and like everyone wanted it gone — I mean really, even the name “spider angioma” was grotesque.

I got older, and the spider angioma became the first entry on a long list of insecurities. My height, my weight, my skin, my face — none of it was good enough for me. It was probably something about those hormones kicking in in middle school, but all of a sudden, I became doubly self-conscious. I had a million different features, and for some reason, I thought every single one of them, physical and mental, was fundamentally wrong and different. If I saw my reflection for more than a passing glance, I would quickly start staring at myself and needlessly picking apart my appearance.

The truth is: just about everyone, everywhere, all of the time is insecure about one thing or another — it’s just human nature. Some people hide it well enough. The rest of us try to reduce it — we make little jabs, we sigh and make self-deprecating comments, and we end up fueling our insecurities ourselves.

People will often try to make you feel better by saying things like “nobody notices” or that they “can’t even tell.” In reality, others do notice features about you — anyone who matters will love those features just as they love you. No, others aren’t blind to the things you perceive as flaws; they see them, and see them simply as another one of your features.

I look back at photos of the mark now and it seems so insignificant. People may have noticed it, but no one would have thought about it in the negative way I was so sure they did. I still have my insecurities like everyone else, but when I do, I just try to take a step back and think: humans have features, not flaws.

The spider angioma on my cheek faded away, and new ones have appeared elsewhere. With time, the blood vessels that made up the red web healed up, and the big spot in the center lost its pigment. The dots that replace it aren’t quite as noticeable — they’re only red specks. What’s more — when I mention them, oftentimes I discover a friend who has one or two themself. It’s transformative, really: the feature I once hated so much has somehow become more unifying than anything.

I’ve learned to live with the spider angiomas; they’re just marks, and they don’t affect my ability to do the things I enjoy or spend time with the people I love.