Freddie Mercury was many things: a native of Zanzibar, a genius poet who boasted a four-octave vocal range, a bisexual man who flaunted his flamboyant demeanor for millions. But he was not cliché. The PG-13 Queen biopic, “Bohemian Rhapsody,” should capture his originality for the duration of its two hour and 15 minute run time.

But alas, sometimes that which should be is not.

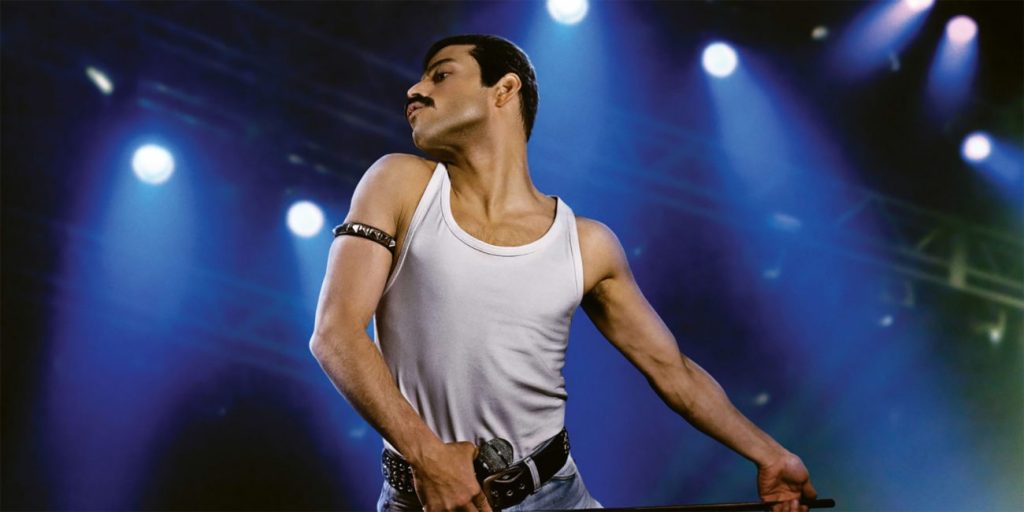

The first half of the film, which hit theaters Oct. 2, is spent trying to cram all of Mercury (Rami Malek) into a neat little box of what has become the great musician archetype. The opening scene features a superstar Mercury pumping himself up to go onstage for his iconic Live Aid performance. The film establishes three conflicts that Mercury struggles with: his sexuality, his music, and his identity, each of which feed off of the others. The film includes countless references to sexual exploration, ranging from a suggestive smile to men dressed in leather straps and masks. His contemplations of identity often relate to both his sexual orientation and his family, for he receives backlash from his father for changing his name and spends the whole film secretly yearning for paternal approval.

This is well and good. So far, there are no blatant overplays of creative license — until conflict arises with his musical career. The writers fabricate a dramatic schism between Mercury and the band in order to make a more dramatic reconnection sequence when the frontman begs for forgiveness and tells Roger Taylor (Ben Hardy), Jon Deacon (Joseph Mazzello), and Brian May (Gwilym Lee) that he has AIDS. All of this drama would culminate in the band’s Live Aid performance, the film’s clean and convenient denouement.

In this portion of the film, it seems as though the writers took hold of the timeline and twisted it into a pretzel to better fit their vision, for Mercury was not diagnosed with AIDS until 1987, and Live Aid took place two years prior.

But the culmination of the biopic’s shortcomings also prove to be its saving grace. A sequence that directly contrasts the opening segment shows Mercury, along with his compatriots, psyching themselves up and walking on stage together. This segment shows the music legend as a team player, showcasing his dependence on the band to humanize him, which challenges the rock star archetype instead of pushing Mercury further into it.

The performance of “We Are the Champions” provides the perfect opportunity for a clean wrap-up that covers the three conflicts of the story, and the writers took this opportunity and made it into a beautifully concise conclusion. But, there are problems that even the most elegant of conclusions cannot mask.

One specific aspect of the biopic is absolutely, unforgivably, and irrefutably infuriating. Not the figurative mile of creative license that the writers and director took when they were given an inch. Not the giant CGI crowd used to recreate Live Aid. Not even the cheap type art and freeze-frame graphics that coincide with a tour montage.

Those sins can be overlooked. But one cannot. Mercury wrote song lyrics out on lined paper. Against the lines. He wrote lines of text perpendicular to the lines on the paper. It is perfectly safe to say that this overlook will be the key deciding factor in whether this film has any longevity whatsoever.

A certain amount of leeway must be granted to the creative teams on these types of projects, but no one should be permitted to tarnish Mercury’s memory by portraying him as a musical savant — a complete neanderthal when it came to lined notebook paper. Though often factually inaccurate, “Bohemian Rhapsody” pays homage to the queen in a fittingly artistic, flashy fashion.