School curricula face controversy, censorship

May 4, 2022

This previously ran in the April 2022 print issue.

In November, amid heated school board elections, Joslyn Diffenbaugh watched how local Kutztown politicians weaponized literature as a means of getting elected.

This controversy was enough to motivate the 14-year-old middle schooler to fight back against their efforts to control and censor what she and her peers can read in school.

Diffenbaugh was first concerned when Texas state representative Matt Krause released a list of books he sought more information regarding. Particularly, he wanted to know specifically how many copies of these books various districts had as well as how much they cost. This list mentioned 850 titles, including 10 referencing Roe v. Wade, and a further six directly mentioning Black Lives Matter in their titles.

According to Diffenbaugh, this controversy reached the Kutztown Area School District school board election when some candidates made unsubstantiated claims regarding the school district’s curriculum. One of the most notable pieces of literature used as evidence by candidates was the picture book I am Jazz.

Written by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings, the book is based upon the real-life experiences of Jennings. Jennings, a 21-year-old transgender woman, is a notable media personality, drawing more attention to the book than it might normally have received.

“The school actually does not have a copy of the book nor lesson plans involving that book or anything on that topic,” Diffenbaugh said.

Inspired by these events, Diffenbaugh started her own movement: a Teen Banned Book Club based out of the Firefly Bookstore in Kutztown. The 8th-grader approached the bookseller with her idea in January; Firefly associate and co-runner of the club, Jordan Busits, quickly endorsed her proposal.

“I have always been an advocate in fighting back against censorship and book banning,” Bustis said. “[I] immediately wanted to support Joslyn’s idea.”

One of the major motivating factors for Busits’ participation was her own personal feelings regarding school curriculums.

“I also consider the lack of historic novels written by women and people of color being taught in schools to be a more subtle form of censorship,” Busits said. “It gives students the impression that only the works of white men should be considered historically valuable.”

The book club has received a mostly positive response from the surrounding community, including donations toward funding their meetings, but it has also received some pushback from local, pro-censorship groups.

“Unfortunately, there is a large presence of Moms for Liberty in Kutztown. Some members have made negative comments about me, specifically that I am just a ‘political pawn,’” Diffenbaugh said. “However, their words are scripted whereas mine are my own. I think that they are intimidated by my willingness to fight for what I believe in.”

Moms for Liberty is an organization that sourced itself nation-wide–its individual local chapters spanning several school districts in that particular area. Moms for Liberty is composed of activists who fight based upon the mission of “parental rights in schools.”

Moms for Liberty Berks County chapter chair Jackie Bridges makes it clear that the organization does not seek to “ban” books deemed inappropriate by their standards — instead, aiming to challenge them.

“I like the word challenging, because it gives room for discussion and is not demanding,” Bridges said. “Traits of books in K-12 libraries that are red flags would be explicit and obscene sexual illustrations and writing.”

The Berks County chapter of this organization has exercised their voices in their surrounding communities — but only twice. The challenged books, All Boys Aren’t Blue and Gender Queer, were flagged for vulgar literautre, potential triggers for victims of sexual assualt, and pornographic cartoons, respectvely. The Berks County chapter makes it clear that these decisions were not made in regards to the sexual oritentations of the characters featured in these books. All Boys Aren’t Blue was ultimately kept by the school; Gender Queer continues to be fought.

Bridges, on behalf of the Berks County chapter, explained her philosophy behind the need for materials in schools to be monitored by parents. Despite believing that teachers and administrators intend to act in the best interest of students, she believes the Department of Education, established in 1979, was created to “run schools more like a business and to train children in the way they want them to be trained.”

“[This approach] takes away from the personalization of individual children and [the] basics of education,” Bridges said. “Children are not one size fits all; they all have different gifts and abilities.”

Bridges supports the movement the Teen Banned Book Club has started, as it is not an in-school program, but most importantly, has encouraged kids to become more interested in reading.

“If the parents have given their blessing for the child to read that content, then so be it,” Bridges said. “If parents would like their children to have those books, there are plenty of other places [besides in schools] to borrow or purchase them.”

The Emmaus High School administration, to an extent, agrees. Laura Witman, Assistant Superintendent, sees the need for diversity.

“There should be great thought into choosing [class novels], and not only just in diversity but also in the level of the text and the vocabulary,” Witman said.

Witman also mentioned the need for students to pick their own books, citing the need to ensure the comfort of students.

“They already have that choice [to avoid feeling uncomfortable] embedded there,” Witman said.

Outside of Pennsylvania, a wave of increased censorship activity has been affecting countless school districts across the country. According to the American Library Association, “Public schools and public libraries, as public institutions, have been the setting for legal battles about student access to books, the removal or retention of ‘offensive’ material, regulation of patron behavior, and limitations on public access to the internet.”

Also published by the ALA, The Library Bill of Rights stands against the attempted pressure exerted on these institutions, with four of the seven principles included focused on stopping censorship.

Librarian Kelly Bower has embodied the Library Bill of Rights in EHS’ library by defending multiple books from challenges — from The Electric Kool-aid Acid Test to Looking for Alaska. Describing her philosophy, Bower ensures that her personal feelings do not play into decisions regarding censorship.

“Just because I don’t believe in something or I don’t feel something’s important, I personally don’t feel like it is my job to shield [the students] from that,” Bower said.

Even more so, frequently referencing the Library Bill of Rights as a cornerstone of her philosophy, Bower understands the important balance she must strike in her role in the Emmaus community.

“I just have to give you the best information I can. I feel that’s my responsibility,” Bower said. “Your parents are paying for me to make those decisions. I can’t take it lightly.”

Former English department chair and current English teacher Diane DiDona feels similarly to Bower, especially regarding freedom of information.

“I don’t like the idea of censoring a curriculum or censoring any particular book,” DiDona said. “I don’t know what is to be gained by pretending that something doesn’t exist.”

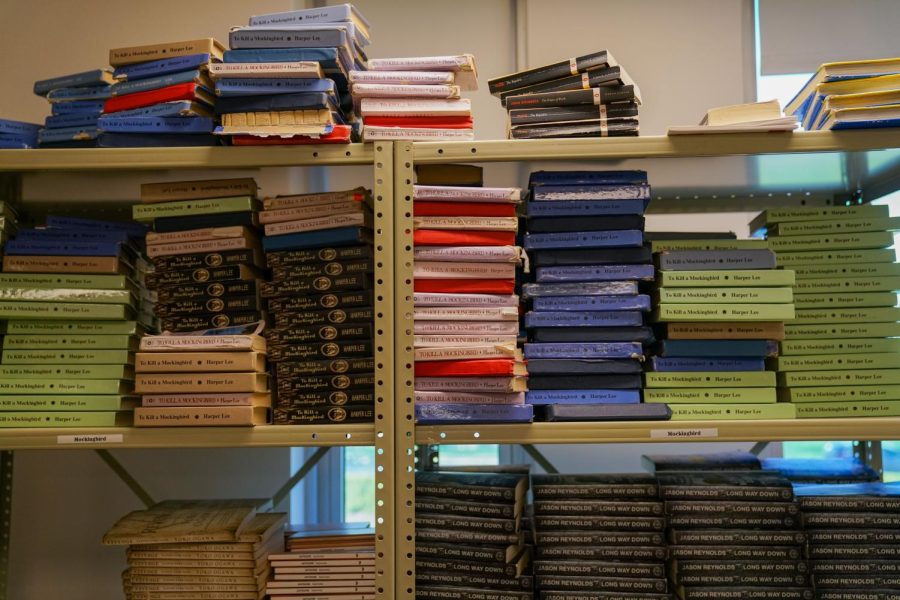

This year’s graduating class, the class of 2022, and the junior class, class of 2023, are among the last students going through Emmaus High School to have read some of these disputed materials within their English courses without challenge. Specifically, these students have read To Kill a Mockingbird and Of Mice and Men.

Amid controversy across the nation regarding these books, they have almost entirely slipped out of the EHS curriculum with little explanation. The number of English teachers including these books in their lesson plans is a fraction of what it used to be. Despite this, many students still recognize the educational value of reading material like Of Mice and Men, including senior Owen Hoffman.

“It was less education in the idea of English education and more just being able to experience people’s mindset at the time,” Hoffman said. “But I think there is still some decent merit to having [Of Mice and Men] in schools”

Still, Hoffman feels it is up to the school’s judgment regarding curriculum choices and is open to scenarios in which it is deemed necessary.

“When it comes down to it, no matter what, it’s up to the school’s discretion,” Hoffman said. “I could see cases where it would be needed.”

Senior Logan Oleksa feels that the choice regarding what students are required to read should be up to themselves and their families; yet, he still believes that students should be able to access any books they want within the library.

“I feel like they should be available [in the library], just for like, so we have the knowledge of them, and if students would like to read them they have the ability to,” Oleksa said. “But again, if it’s just in the library, no one is being forced to read them.”

Even if which books it includes is in question, DiDona feels that the school curriculum will always need literature.

“Depending on the person, I think literature can change your life. For some people, literature is literally a way to experience the world,” DiDona said. “I think literature presents us with universal human experiences and gives us an opportunity to make connections across cultures. So, I think literature really does have a place in the curriculum.”