This previously ran in our April 2023 print issue.

By the age of five, junior Kayla Gonzalez confronted a reality that many students, parents, and teachers fear: a school shooting.

When Gonzalez was in kindergarten at a public school in Wilkes-Barre, a gang shooting outside the building sent the classes into lockdown. She remembers bits and pieces of the event and mainly recalls the associated feeling of fear.

“I can’t really remember most of it… but I do remember what they call lightbulb moments,” Gonzalez said.

She remembers picking up on her teacher’s fear, feeling confused and afraid.

“[The teacher] looked panicked,” Gonzalez said. “She hid under her desk right behind us. And I remember she [said], ‘Quiet. Just be quiet. Be quiet, be quiet.’ And I remember we’re just sitting there for, I think, an hour and then finally we got out.”

Gonzalez’s traumatic experience was not unique. Across the country, schools — especially schools in underprivileged areas like Wilkes-Barre — face the threat of gun violence. The quantity of school shootings per year has increased dramatically since 2018, with the number having steadily risen over the recent two decades.

The problem exists outside of the classroom, with firearm-related crimes making up 79% of all crimes in the U.S., according to the Pew Research Center. A 2020 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that 50 people in America die from gun violence every day, 20 percent of which are under 18 years old.

Having been exposed to gun violence at a young age, Gonzalez believes firmly in stronger gun regulation, and mentioned the fear that many students feel in school, as well as a larger normalization of gun violence in the country.

“At such a young age, you have to worry about [shootings],” she said. “I definitely think gun culture in America is very normalized when it shouldn’t be. You shouldn’t have to worry about if you’re gonna get shot today at school. You shouldn’t have to worry about, ‘Oh, I need my phone because what if I can’t text my mom [that] I love her?’”

As Gonzalez said, the gun violence epidemic is a uniquely American struggle, faced by no other industrialized countries to this scale. Critics suggest that gun ownership in the United States faces loose regulations compared to other countries with lower rates of firearm violence, and proponents of stricter rules believe this status lends itself to unnecessary casualties. Compare this to other countries’ stances on gun control, especially in Asia.

In July of 2022, a lone gunman walked up to Japan’s former Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, as he delivered a public speech and despite the security detail present at the scene, pulled out a weapon resembling a sawed-off double-barrel shotgun.

The gunman fired two shots, one of them penetrating the victim’s neck and chest. He was then taken to a hospital, where he was soon pronounced dead. The assassination caught the world by surprise, largely because Japan has one of the lowest gun violence rates globally, so a public murder such as this one came as a horrific anomaly.

But the murder also shocked because of the weapon: the killer made it himself.

To own a gun in Japan means passing a written test and attending a day-long class (both to be retaken every three years), and finishing a shooting accuracy test with at least a 95%. The government conducts mental health evaluations and background checks, which include interviews with people close to the buyer. Guns belonging to the deceased are turned in by family, and the amount of operating gun stores allowed in the nation is severely limited. A gun owner can only buy a new magazine by bringing in an empty one. Police forces tend to trade out guns for martial arts and striking weapons, and the officers that do carry guns are only permitted to do so when they’re on the clock.

With a long history of strict gun laws, Japan managed to prevent guns from becoming a deeply rooted part of Japanese culture. They are rarely used in sports or hunting and in very few houses can they be found at all. Firearms are not a feature of everyday life in Japan.

The United States is a different story.

Even in nations with yearly firearm incident rates surpassing that of the U.S., guns are typically a way of responding to poor treatment by the authorities at large and unfortunate, cyclical conditions of poverty. Though this is often true in the U.S., the nation contains something that few other countries see: a culture highly intertwined with guns.

EHS Resource Officer Al Kloss recalls the popularity of gun ownership during his high school years, and remarks on the normality of storing them in cars throughout the school day.

“Back in the day, this was all farmland and guys would actually come to work or come to school with a shotgun in their car because they would go out hunting after school let out,” Kloss said. “And that was accepted — that was normal.”

According to Statista, around 45% of American households are home to one or more guns, and the U.S. has the largest amount of firearms in civilian hands out of all the countries across the globe. The Small Arms Survey, an organization dedicated to documenting gun violence and illicit firearms dealings, claims that there are approximately 120 guns per every 100 citizens in the U.S.

Intention in gun ownership varies considerably. Firearms can be used as a means of providing food or as a pastime – hunting and sports that involve shooting are popular.

Freshman Frank Colosimo sees firearm hunting as an integral part of his personality, and thinks that his experiences hunting have made him a more responsible person.

“I feel that if I didn’t have hunting, I really wouldn’t be myself today,” Colosimo said. “I feel like if I didn’t have a gun and like to be able to hunt and have that experience, I feel like I wouldn’t be as responsible as I am.”

While he feels that shooting is a part of his identity, Colosimo also believes in ensuring that guns wind up in safe hands.

“I think guns should be legal but think all the rules and laws are fine,” he said. “When you get a gun, you should definitely have a background check.”

He emphasized the importance of understanding how dangerous guns can be.

“You must know what that gun is capable of doing,” Colosmo said. “It is a weapon; it can kill. So [you] need to be able to know what that gun could do and control it.”

In many marginalized communities, guns are used for protection by some and for violent purposes by others; purposes which include drug-related offenses, theft, and gang activity.

This looming presence lends itself to deaths and injuries of many kinds, both intentional and accidental. According to 2023 data from the World Population Review, about 11 firearm-related deaths occur for every 100,000 citizens in the United States alone. This number remains surpassed only by certain Latin American countries, which are prone to violence due to the existence of violent gangs, unstable governments, and major drug trafficking industries.

Firearms are deeply entwined with U.S. history, beginning as early as the creation of the country itself. During the Revolutionary War, armed citizens made up a militia that was called for in the absence of a national military. Starting at this time and continuing on, guns have been a cherished symbol of freedom and rebellion against tyranny – as is evident in the Second Amendment.

When Congress passed the Second Amendment, the weapons and technology at the time were rudimentary and oftentimes inaccurate. Firearms of this period required much effort and time to operate and carried few bullets.

Even outside of wartime, gun ownership was seen as a simple fact of life. For many young boys, it was often a symbol of wealth and prosperity as well as a rite of passage. According to the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, about half of all American households owned a working gun and remained that way up until the 1960s.

Hunting was seen as an honor, a way to provide food for one’s family. Hiram Maxim invented the first automatic weapon in 1884 and only became popular during World War I. In the early 1900s, 43 states restricted or completely banned carrying firearms in public.

The first true wave of gun violence awareness came with the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr, and Robert Kennedy throughout the 1960s. Their deaths pushed for the Gun Control Act of 1968, which regulated firearm ownership and its industry. Bills like the Brady Act in 1993 and the Federal Assault Weapons Ban in 1994 were passed to deter rising numbers in violence. The Brady Act made it a requirement to wait five days for a licensed seller to sell a handgun to an unlicensed person while the Federal Assault Weapons Ban outlawed 19 types of weapons. Both the 1968 and 1994 bills expired in September of 2004 and were never renewed, leading to a shift in attitudes towards guns. A poll in 1999 reported that only 26% of gun owners kept firearms for protection and self-defense as opposed to hunting and sport. This percentage rose to 63% by 2015 according to John Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health.

Today, it is estimated that 3 million Americans carry loaded handguns in public each day according to John Hopkins Center for Gun Violence. Since 2004, gun-related deaths have risen by 45% and in the past two years, firearm deaths increased by more than 25% nationwide.

That being said, Emmaus is a relatively safe community. In 2016, the FBI reported 324 crimes in Emmaus, 88% of which were theft and property crime. In a town of over 11,000, this is fairly tame. The constant threat of violence present in certain disadvantaged areas is not present within the borough; students can walk to school and stroll around the Emmaus Triangle without the concern of drive-by shootings or gang activity.

Most firearm-related incidents in Emmaus are gun thefts, according to Kloss. Thieves steal guns from the homes and vehicles of Emmaus residents and sell them in center city Allentown, then trickle into Reading and Philadelphia. Thus, Emmaus acts as fuel to fires that exist elsewhere, while not being particularly burned itself.

Kloss remarked on how weapons robberies affect nearby communities.

“It comes and goes in spurts, but we’re seeing a lot of gun thefts,” Kloss said. “[The thieves] are looking for handguns, [which] get sold in the city — in Allentown and Reading, and they make their way down to Philadelphia. That’s a big problem here in Emmaus.”

Mass shootings, and school shootings in particular, have spiked dramatically after the pandemic, with 2022 having the most school shootings since 1999, the year the Columbine shooting occurred, according to the Sandy Hook Promise. Over the years, many high schools across the nation, including EHS, have put in safeguards to try to prevent the penetration of gun violence into their schools. These policies include ID checks, restricted entry, and a locked-door policy – the latter two of which were introduced to Emmaus High School this year.

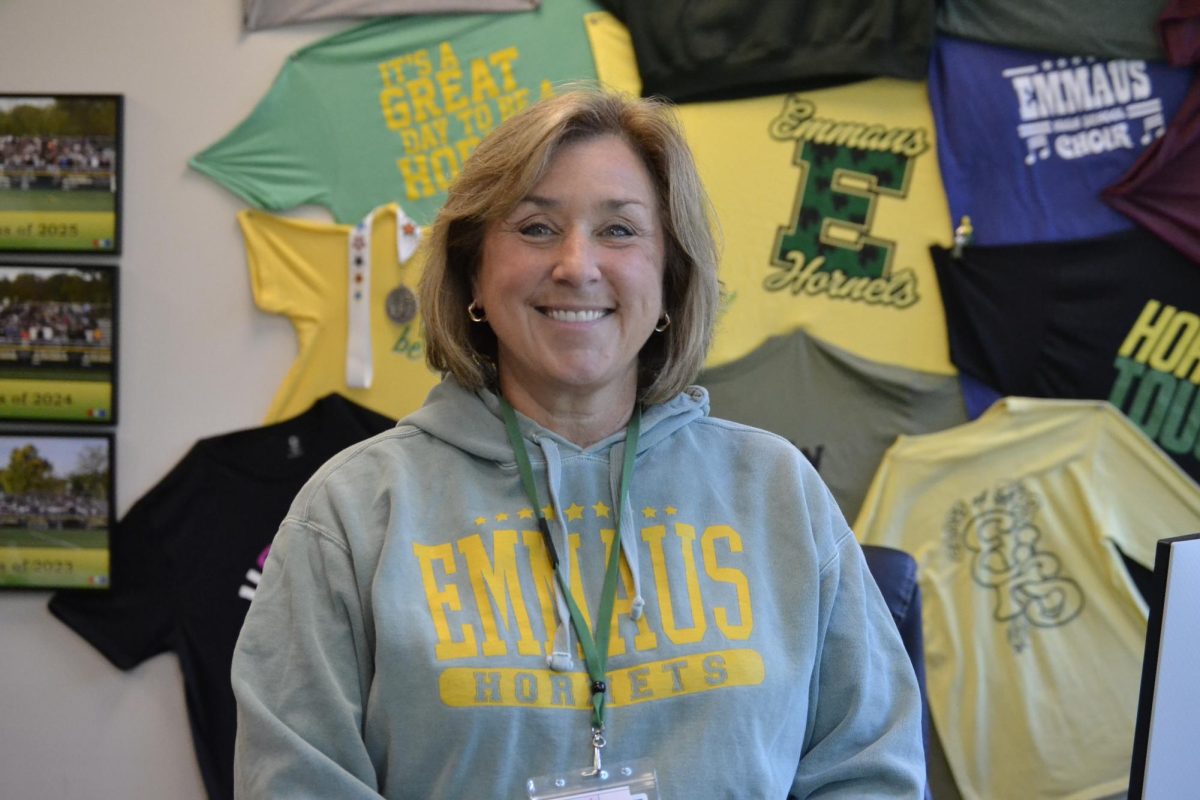

EHS Principal Beth Guarriello explained some of the measures put in place to prevent threats to student safety in schools.

“Unfortunately, because of the world we live in, we have to take additional measures that we didn’t have to take even 10 years ago,” she said.

She added on by describing safety measures she would like to see implemented across the school within the next year.

“I would like to add another layer [of security] next year,” she said. “I’d like to add alarms because I’m not naive enough to know that kids are still propping the doors, and we’re finding doorstops in the exterior doors and kids are coming in and out [of the building].”

In addition to putting more security measures in place to protect the building in case of a threat, Guarriello believes part of the solution is fostering relationships and a sense of community within the school.

“We can certainly make the school safer with, you know, fewer fights and fewer conflicts, if we take the time to get to know each other,” Guarriello said. “That is the reason behind the Hornet Homeroom activities … if you get to know people, you’re less likely to hate them.”

Solutions aside, Guarriello believes that current culture varies greatly from that which she has seen over the course of her life as both a student and an educator.

“[Now] everything just seems a little bit more scary,” she said. “I think the stuff that you guys are dealing with is much more serious… and mental health issues are tremendously more. The drugs are definitely more dangerous. It’s tough.”

She remarked on specific dangers faced by modern generations that were not always present, including increased risks associated with drug use, as well as phone usage; more specifically, cyberbullying.

She also believes that students coming out of the pandemic have been socially stunted by the unrelenting use of technology for the past few years.

“I do think the phones and the technology have created more isolation … the skills to deal with conflict have been drastically reduced because everybody’s hiding behind their phone[s],” Guarriello remarked.

According to a 2020 analysis done by the Secret Service, the most common motives for committing a school shooting were “grievances with classmates or staff” and experiencing bullying.

Kloss also believes school outreach is important in order to create a safe environment in which students feel welcome.

“One of the reasons I’m here is to break down the attitudes towards the police. We get dialogue going, you know, tearing down those walls,” Kloss said. “I think I do a lot more to keep kids out of trouble than actually get them in trouble. I have a lot of things at my disposal that I can [use to] keep people — keep kids — out of the criminal justice system.”

In January, two shootings rocked the state of California; those in Half Moon Bay and Monterey Park, with a combined 15 deaths and 10 non-fatal injuries. President Biden responded by promising to issue an executive order that will mandate stricter regulations on gun ownership.

This follows a 2022 bill passed by Congress, which strengthened background checks for 18- to 21-year-old buyers, restricted ownership for domestic assault offenders, set up grants for states to remove guns from criminal offenders, and funded mental health and safety programs in schools. The bill was a response to the shootings in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo, New York, which were both committed by 18-year-old men; between the two shootings, 31 people were killed (including the shooter at Uvalde) and 21 were injured (including the Uvalde shooter’s grandmother, who was at home when she was injured).

In the first three months of 2023, the nation has witnessed 119 mass shootings and more than 9,500 deaths due to gun violence, and gun violence is the leading cause of death for people under the age of 18. The role of gun violence in the nation is heavily debated across the political spectrum, and persistence on both sides has locked the government in a stalemate.