This story previously ran in our April 2023 print issue.

“I felt angry, depressed, and kind of betrayed.”

These emotions marked the experience of senior Jamie Doe* in grades five, eight, and nine, a time period during which food insecurity prevailed in their life.

As defined by Feeding America, a nationwide food bank network, food insecurity is “the consistent lack of food to have a healthy life because of [one’s] economic situation.” This condition persists in the lives of 34 million Americans, and of these individuals, nearly 1.1 million reside in Pennsylvania.

Hunger—the body’s natural response to a lack of food—poses numerous obstacles to any human. As Penn Medicine explains, hunger not only generates a variety of physical symptoms, such as shakiness and headaches, but can also affect one’s mood.

“It was really lonely,” Doe said. “I was just exhausted and bored a lot.”

While food insecurity affects each person differently, its consequences are inherently damaging. For the nearly 400,000 food-insecure children in Pennsylvania, these consequences become especially detrimental to the environment in which they spend the most time: schools.

“… if a basic need such as food is not met, [students] are not ready for learning,” Anthony Moyer, the principal of Willow Lane Elementary School, said.

Thomas Ruhf, the principal of Eyer Middle School, also highlights the link between provisions and school performance.

“The school is a sum of all parts,” Ruhf said. “If [a student] comes into school with their basic needs not met, it makes it really hard to be successful.”

Aside from learning, food-insecure students face additional social challenges as they form friendships and interact with peers.

“I did not have people over to my house at all,” Doe said. “Because if people come over, I can’t feed them.”

Doe also described how food insecurity affected their peer relationships more than other aspects of adolescence.

“I remember one time I was talking to a few of my friends, and I mentioned something about not having food in the house,” Doe said. “They got, like, really concerned about it, and I just felt like, ‘Huh, I guess that’s not normal.’”

It’s no surprise that food insecurity is a big problem in American schools– the EHS Angel Network, which assists economically-disadvantaged students, has been around since 2004. However, not all age groups experience it in the same ways. For middle and high school students, food insecurity coincides with their emotional development as adolescents. As they cultivate their identity, they often become more aware of socioeconomic status, with food insecurity included in this consciousness.

“… middle school students start to make that move away from their parents … and become more independent,” Ruhf said. “They might start to understand at a greater level of self-reflection that they are experiencing food insecurity, and … that could lead to some big feelings.”

When compared to older students, elementary school kids are less aware of food insecurity as a nationwide concern, seeing the world through a young, naive lens. This affects their ability to communicate freely about food insecurity, as younger children tend to lack the “social filter” that drives older children to hide their socioeconomic struggles.

“[Elementary students] don’t get embarrassed to say that they don’t have [food],” Suzanne Vincent, the principal of Macungie Elementary School, said. “I think elementary kids are more likely to tell their teacher that they’re hungry, and their teacher usually has some cabinets full of snacks that they can share with them.”

At varying grade levels, differences in food insecurity do not end at the student psyche. Within the EPSD, attitudes towards students can also change with age group.

Often, middle and high school students are viewed as the “grown-ups” of the student body, with their needs overlooked in sight of the younger population. The district’s previous lunch debt policies reflect how older kids are seen through a biased lens.

“All kids need the food, but high school kids certainly do, too,” Vincent said. “… high school used to be, if you had debt, you would get no food. At the middle school, you would get a cheese sandwich. At the elementary school, it didn’t matter about debt– kids always were fed.”

As the district has grown, these policies no longer exist. Vincent reports that this grade-dependent lunch system disappeared around 2015. In 2023, if a student lacks lunch funds, they are still served a full meal, albeit putting them in debt.

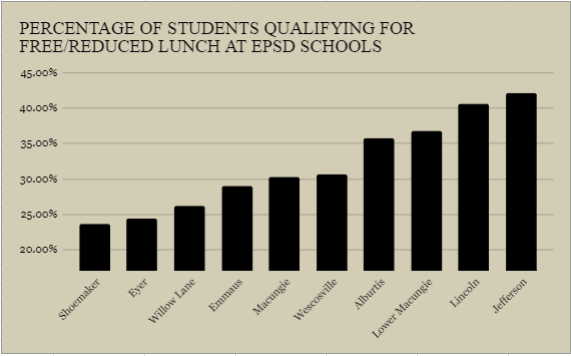

Still, the number of students who qualify for free or reduced lunch is alarming.

Within the entire EPSD, Jefferson Elementary School has the highest percentage of students qualifying for free or reduced lunch at 42.18%. Coming in second to Jefferson, 40.65% of students at Lincoln Elementary School qualify for the need-based program.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, less than a quarter of students qualify for free or reduced lunch at Shoemaker Elementary School and Eyer Middle School, with percentages of 23.65% and 24.45%, respectively.

When considering the broader picture, the proportion of students qualifying for free or reduced lunch has increased over the past year.

From 2018 to 2021, this value stood at a constant 27%, even through the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. In 2022, however, the rate increased to 29.91%. Although a miniscule change, it could mark the beginning of an increase for the coming years.

In addition, the district’s lunch debt stood at an overwhelming $32,805, even with the aid program implemented. This value reflects the cumulative lunch debt of all EPSD students as of March 20, 2023.

With these vast concerns in mind, there has also been a great push to combat food insecurity– both within the district and throughout Pennsylvania.

Before Oct. 2, 2022, a cost was associated with school breakfast– one contributor to the district-wide lunch debt.

Now, thanks to legislation passed by former Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf, qualifying school districts have been granted funds to supply free breakfast. Between Wolf’s breakfast legislation and the district’s own free/reduced lunch program, more students are guaranteed two meals a day. Overall, an average of 1,344 EPSD students utilize the free breakfast program per day.

“…the free breakfast program that the governor has put in place is great,” Moyer said. “Because at least we know if children don’t have anything at home, they’re coming here and at least they have food…”.

Even with legislation and district-implemented programs, there still remains an overarching need for food resources. The East Penn community often heeds the call to do more. For example, Willow Lane Elementary School manages a school-wide garden. Its crops serve to combat food insecurity on a community level.

“As you know, because of our seasons here in the Northeast, when we have the greatest harvest is the time when students aren’t here,” Moyer said. “So, what we typically do is donate the produce that we yield to the Sixth Street Shelter in Allentown.”

Moyer explained that the Sixth Street Shelter supports homeless mothers and their children, aiming to provide healthy alternatives over canned or fast food options.

Willow Lane’s efforts do not stand alone in the fight for community food security– Trexlertown’s Giant joined the cause in early March. The grocery store donated over $12,000 to the EPSD through the three-year-old “Feeding School Kids” initiative, which promises over a quarter of a million dollars to nationally combat childhood hunger.

Among the organizations aiding district-wide food insecurity is the EHS Angel Network, an anonymous donation organization that provides food, school supplies, and prom resources to high school students in need.

Specifically, the organization runs a Holiday Food and Gifts program over winter and spring holidays. After collecting non-perishable items through EHS clubs, volunteers assemble over 150 boxes, whose contents can be used to cook family meals.

“…every family receives a basket full of pantry items, and there’s over 40 items in each box,” Laurie Fine, the food coordinator at the EHS Angel Network, said.

Along with the Angel Network’s baskets, they also supply families with gift cards for the purpose of food shopping. After COVID-19, gift cards have prevailed over food drives.

“It just makes it easier for us to do gift cards now than to buy specific items and manage [food drives],” said Fine.

In order to supplement their Holiday Food and Gifts program, the EHS Angel Network relies on school clubs to run food drives. Typically, each EHS club collects a different non-perishable item – boxed pasta, jarred sauce, canned vegetables – and the donations are collectively added to each family basket. Additional donations originate from sports teams, local churches, and service groups.

“The donations are all coming from small groups, community organizations, school teams, school clubs, small churches, things like that,” Fine said. “It’s really the community giving back to support.”

One of these essential donation contributors is Key Club, a high school volunteer group. Alex Dolcemascolo, the club’s president, explains its previous contributions to the Angel Network.

“Our club’s mission is to provide for our surrounding community and benefit it as much and as often as possible,” Alex Dolcemascolo. “Organizing collections of food items is such a simple way for us to do so … Key Club has worked with the Angel Network to [collect] items such as canned goods, boxed mac and cheese, and other non-perishables.”

Between the Angel Network, student clubs, Willow Lane Elementary School’s garden, and numerous other efforts to mend the damages of food insecurity, Vincent expresses the significance behind these initiatives.

“It matters because we’re a community together,” Vincent said. “We want our kids to learn to help others, and we can set that example to help others, because [food insecurity] all has an impact on us, one way or another.”

*Jamie Doe is a pseudonym. The student’s name has been changed to maintain confidentiality.